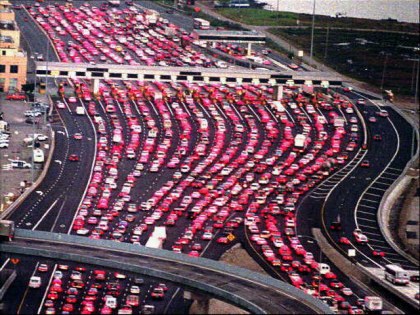

Between the hours of 6am and 10am, the Bay Bridge is miserable. Which is a particular shame, because that’s when everyone wants to use it.

Right now congestion on the bridge adds 22 minutes to my trip to SF. (Using BART would add a comparable amount.) Google’s “typical” traffic estimate is between an 8 and 53 minute rush hour delay.

This is a big problem: here is an estimate of 4 million hours / year destroyed directly by delays, and many more people would use the bridge if they could. If you think that increasing SF housing supply would have big benefits, I think you should expect increasing throughput over the bridge to have a meaningful fraction of those benefits (for example, it looks like 40% of people who work in downtown SF commute from the east bay).

As far as I can tell, fixing the problem would require no new technology, no new infrastructure, and no new spending. It wouldn’t require complicated policies. It wouldn’t even really require creating many winners and losers. It would just require being more sensible.

Now most of the time when something looks like a really great idea it’s because you are missing something. So what I’m really asking is: what am I missing?

The average car on the bridge appears to carry about 1.5 people (divide the numbers in table 2 here; this is from 2009, but it looks roughly right from glancing around the bridge).

If the average could be increased to 2.5, the throughput of the bridge would be increased by two thirds. That is enough to completely eliminate traffic on the bridge and/or dramatically increase the number of commuters.

2.5 is a very big number, but ridesharing apps have made carpooling almost offensively simple. At this point the logistical cost has been reduced to the actual time spent driving around picking people up. We can already put together 2 or 3 destination commutes with 5-10 minutes of extra cost per person (and often less). Because the cost is dominated by having to go out of your way, they would fall significantly if carpooling were adopted at scale for the transbay commute.

The problem seems to be that carpooling creates a whole bunch of social value, but almost all of it goes to people other than the carpoolers. (To get a sense for the value: if everyone carpooled there would be negligible traffic, so you are paying 5-10 minutes per person to save >20 minutes per person. The value per carpool is even higher when there are fewer of them.)

Tolls

One response is to lament human greed and laziness. But being as we are creatures of reason we could instead take a more effective approach. Here’s an alternative:

- We charge a market clearing toll. I don’t know how big that is: $15? $25? I don’t know anything about traffic, but the situation is sufficiently straightforward that it doesn’t matter much for the cost-benefit analysis.

- By “market clearing” I mean high enough that there is basically no rush hour congestion. You just keep raising the price until the bridge isn’t too crowded, it’s guaranteed to happen eventually. I’d have to actually know something to guess exactly how minimal you can make the rush hour delay, but I expect the average can be < 5m. (The non-zero delay is caused by fluctuation in demand that isn’t matched by fluctuation in tolls.)

- People carpool over the bridge en masse. If there is a $20 toll, few people are going to drive over the bridge alone during rush hour.

- We create something like 2-4 million hours/year of value for commuters before we even consider the increased throughput.

- We raise a boatload of extra revenue.

Note that tolls would be imposed only on the westward trip, but that would directly decrease the cost of return trips, and would also eliminate congestion on the roads that feed into and out of the bridge. Ridesharing services are strongly incentivized to split the cost of the toll between the two directions.

Access and upwards redistribution

One concern is that tolls decrease access for low- and middle-income commuters even if they improve overall efficiency. I don’t really believe this story though, unless someone can explain to me why the naive picture is wrong:

- Consider someone who takes the bridge each day. They are paying $6 to get across the bridge right now, and perhaps another $5 of gas and wear-and-tear for their commute (20 miles * $0.25/mile seems optimistic). Call it $11 total.

- If we increase the toll to $15 they’d instead face a total cost of $20 for their round trip.

- If the people could double up, they would be back to $10/person. Even if they were already carpooling, cars can easily sit 4, so pairs who are currently carpooling could merge into large carpools at the same additional cost.

- They would pay an additional cost for carpooling: the time required to pick more people up and drop more people off. This cost is perhaps 10m per person per day, though I think it would be smaller if there were better scale economies.

- These time costs are way more than offset by lower wait times on the bridge.

- Everyone ends up with more money and more time. Throughput on the bridge is increased. The state makes a bunch of money. Whatever companies get to take a 20% cut of the action are thrilled. It’s hard to find the big losers (parking garages in SF?)

Some possible issues

One possible downside is that people don’t like carpooling with strangers. My personal experience of carpooling with strangers has been so non-interactive and inoffensive that I find it hard to imagine this being a huge problem (even if pairs are merging rather than individuals, and even if they want to talk to each other). It’s even harder to imagine when I compare the user experience of BART vs. carpooling and reflect on the fact that BART services about half of rush hour trips. If this is really the billion-dollar bottleneck, we could/would also make a more serious effort to fix it, e.g. by improving carpool matchmaking, installing limo privacy dividers, changing norms for carpooling interaction, or something else.

Another possible downside is that people really want their cars in SF. But if people really need to move around in SF during the day, the cost of ridesharing within the city is not too much more than the cost of parking (unless you are benefiting from subsidized parking or need to move around a lot). And you only need about half of people to be willing to skip having their car in SF.

I find travel times across the bridge reasonably consist, but there is definitely variation, and a lot of value is destroyed by accidents and abnormally long delays. In principle these can be handled by dynamic tolls–when capacity goes down, tolls go up, and hopefully somewhere there are enough drivers who can respond adaptively to higher tolls in order to make the market clear again. (This is way more plausible in the era of ridesharing, where the necessary “adaptivity” may just mean chossing a different button in your ridesharing app when it warns you that your normal commute would cost an extra $5.) But if we are just focusing on drop-dead-simple policies that wouldn’t be potentially confusing and rage-inducing, then we probably can’t do this kind of dynamic congestion pricing. This may limit the possible upside of tolls, and maybe I am being too optimistic when I imagine rush-hour traffic being completely eliminated with only a modest reduction in vehicle throughput.

Really big tolls

If we would need a really big toll to make the market clear–say a $35 per car–then access becomes a more real concern. You would need 4x larger carpools to keep the price down to current levels, which for people who are already carpooling would basically require vans.

I have no idea how likely this is. But it’s worth noting that in this case every car we take off the bridge is adding $35 of value (since that’s the marginal price people are willing to pay to put a car on the bridge). So anyone for whom the toll is an issue really really should be going in giant carpools.

But this creates a legitimate distributional issue.

I think the most likely scenario is: a bunch of people used to be unwilling to use the bridge because it took forever. Once traffic comes down, these people come out en masse and soak up all of the capacity created by carpoolers. Maybe people move out of SF into the rapidly-gentrifying Oakland, saving $800/month on rent in exchange for $400/month in tolls. Maybe we create new jobs in SF. I don’t know.

In any case, the 2016!commuters are now carpooling and are still worse off than before. The extra value is flowing to the state in the form of massive additional toll revenue.

My best solution would be to straight-up cap the toll for 3+ person carpools at something short of $25. Combined with a market-clearing toll on low-occupancy vehicles, this is almost certainly enough to eliminate traffic (unless the 3+ person carpools single-handedly cause congestion, which seems highly unlikely). Then this can probably guarantee that everyone benefits, since tripling up makes the average cost lower, and the time costs can probably be more than offset by the reduced congestion.

This makes the policy a bit more complicated and risks messing up the toll plaza. But given that we have historically had a different toll on high-occupancy vehicles, I think it’s not at all beyond the pale.

Another scenario where tolls need to be really high is where people just really don’t want to carpool, and so you even once the toll is $20 people aren’t doing it. In that case, the entire proposal of market-clearing tolls is going to create as much value, and is probably (politically) screwed.

Tolls are awesome even without carpooling

This post focused on the benefits of carpooling, but it’s worth pointing out that from an economic efficiency perspective, tolling would be a really good idea even without the possibility of carpooling. Time people spend wasted in congestion is completely burned value, and transforming it into revenue for the state is already one of the freest lunches around. Realistically that’s impossible for political reasons–you could give the extra toll income back to low- and middle-income families, but you can’t give it back to exactly the same families (and even if you could, someone else would have some different idea about what to do with that money) so no way you are going to get that to work. Carpooling just changes the calculus from “really good” to “crazy good,” and also potentially turns the whole thing into a Pareto improvement.

Conclusion

I’m probably missing or miscalculating something, if you manage to spot it please let me know, but on paper this sounds like a huge amount of value sitting on the table. If it really is a huge amount of value sitting on the table, it’s interesting to think about what is going wrong. My best guesses are these:

- High tolls are unpopular, because who wants to pay more for stuff? People feel way better about being unable to use the bridge because it is crowded, then being unable to use the bridge because some politician decided to greedily exploit control over the bridge to raise some revenue.

- Obviously you would try to adjust things slowly to warm them up, but still there is going to be some initial friction and growing pains, and you are going to at least temporarily piss some people off.

- People don’t like to change what they are doing, and they extra don’t like it when politicians force them to change what they are doing, regardless of whether someone tells them it’s for their own good. Especially if you cap the toll for large carpools, this policy may be perceived as mandating carpooling + imposing a punitive toll on non-carpoolers.

- Raising more revenue generates a bunch of debate about what to do with the revenue, so policy change might be hard even if literally burning the value would be an improvement over the status quo.

- Raising tolls is basically guaranteed to significantly increase efficiency, but there is a risk that it will have upward redistributive effects, and it’s politically hard to offset them with the revenue.

- Actually implementing market-clearing tolls is a bit technically challenging, and moreover you are going to look like a total idiot if you mess it up and the bridge runs at only 70% of capacity while everyone is freaking out about how to get into SF.

That said, there are also some things that high tolls have going for them politically:

- Decreases automobile use and makes cars more like public transit, which people on the idealized left should like.

- Rationalizes the market for transbay transport, which people on the idealized right should like. Realistically it substitutes private solutions for an expansion of public transit.

- Huge source of government revenue, which politicians probably like.

- Benefits employers in SF and carpooling middlemen, who presumably have some political weight.

The upshot is, now I am going to be even more frustrated next time I find myself sitting in traffic on the bridge.

You’re basically spot on. That’s what the research seems to say, at least. (But you can either do it as congestion pricing, or a cordon toll.)

See, for instance, this RAND report on how to fix LA traffic;

http://www.rand.org/capabilities/solutions/creating-policies-to-get-los-angeles-moving.html

I agree a toll is a good idea here. Your points about throughput ignore existing research on vehicle flow rate though. If you want to maximize worker supply you probably want to maximize flow. 64 kph seems to give the maximum.

https://people.hofstra.edu/geotrans/eng/methods/highwaysfd.html

Click to access chap2.pdf

http://jliszka.github.io/2013/10/01/how-traffic-actually-works.html

Of course, you can decide what the social value maximizing equation of speed and flow is. On a separate note, do you have any evidence that tolls increase vehicle occupancy? The friction of finding a carpool seems likely to dominate, to me. After all, carpooling already has significant benefits (splitting gas, driving effort, HOV lane)

It seems like setting speed is totally independent (I guess it makes the commute a tiny bit slower at peak times, but the bridge is pretty small and it’s not going to be more than a 1-2 minute delay).

Carpooling isn’t super common now, but still lots of people do it, and we are discussing tripling the benefits. I don’t have evidence on the effects of large toll increases, but if there were any way to take that bet I would do it in an instant.

I’ve taken Uber and Lyft carpools across the bridge which added a few minutes of complexity, it seems that organizing a carpool is no harder than that (for example, we could use exactly the same process but the app tells one of us that we have to drive, and dynamically adjusts the “riding cost” / “driving cost” in order to make the market clear).

You could probably make this far more palatable by changing the optics to focus on incentivizing carpooling. Rather than just charging a big toll, charge a bigger toll for single occupancy vehicles.