For most people I don’t think it’s important to have a really precise definition of integrity. But if you really want to go all-in on consequentialism then I think it’s useful. Otherwise you risk being stuck with a flavor of consequentialism that is either short-sighted or terminally timid.

I.

I aspire to make decisions in a pretty simple way. I think about the consequences of each possible action and decide how much I like them; then I select the action whose consequences I like best.

To make decisions with integrity, I make one change: when I imagine picking an action, I pretend that picking it causes everyone to know that I am the kind of person who picks that option.

If I’m considering breaking a promise to you, and I am tallying up the costs and benefits, I consider the additional cost of you having known that I would break the promise under these conditions. If I made a promise to you, it’s usually because I wanted you to believe that I would keep it. So you knowing that I wouldn’t keep the promise is usually a cost, often a very large one.

If I’m considering sharing a secret you told me, and I am tallying up the costs and benefits, I consider the additional cost of you having known that I would share this secret. In many cases, that would mean that you wouldn’t have shared it with me—a cost which is usually larger than whatever benefit I might gain from sharing it now.

If I’m considering having a friend’s back, or deciding whether to be mean, or thinking about what exactly counts as “betrayal,” I’m doing the same calculus. (In practice there are many cases where I am pathologically unable to be really mean. One motivation for being really precise about integrity is recovering the ability to engage in normal levels of being a jerk when it’s actually a good idea.)

This is a weird kind of effect, since it goes backwards in time and it may contradict what I’ve actually seen. If I know that you decided to share the secret with me, what does it mean to imagine my decision causing you not to have shared it?

It just means that I imagine the counterfactual where you didn’t share the secret, and I think about just how bad that would have been—making the decision as if I did not yet know whether you would share it or not.

I find the ideal of integrity very viscerally compelling, significantly moreso than other abstract beliefs or principles that I often act on.

II.

This can get pretty confusing, and at the end of the day this simple statement is just an approximation. I could run through a lot of confusing examples and maybe sometime I should, but this post isn’t the place for that.

I’m not going to use some complicated reasoning to explain why screwing you over is consistent with integrity, I am just going to be straightforward. I think “being straightforward” is basically what you get if you do the complicated reasoning right. You can believe that or not, but one consequence of integrity is that I’m not going to try to mislead you about it. Another consequence is that when I’m dealing with you, I’m going to interpret integrity like I want you to think that I interpret it.

Integrity doesn’t mean merely keeping my word. To the extent I want to interact with you I will be the kind of person you will be predictably glad to have interacted with. To that end, I am happy to do nice things that have no direct good consequences for me. I am hesitant to be vengeful; but if I think you’ve wronged me because you thought it would have no bad consequences for you, I am willing to do malicious things that have no direct good consequences for me.

On the flip side, integrity does not mean that I always keep my word. If you ask me a question that I don’t want to answer, and me saying “I don’t think I should answer that” would itself reveal information that I don’t want to reveal, then I will probably lie. If I say I will do something then I will try to do it, but it just gets tallied up like any other cost or benefit, it’s not a hard-and-fast rule. None of these cases are going to feel like gotchas; they are easy to predict given my definition of integrity, and I think they are in line with common-sense intuitions about being basically good.

Some examples where things get more complicated: if we were trying to think of the same number between 1 and 20, I wouldn’t assume that we are going to win because by choosing 17 I cause you to know that I’m the kind of person who picks 17. And if you invade Latvia I’m not going to bomb Moscow, assuming that by being arbitrarily vindictive I guarantee your non-aggression. If you want to figure out what I’d do in these cases, think UDT + the arguments in the rest of this post + a reasonable account of logical uncertainty. Or just ask. Sometimes the answer in fact depends on open philosophical questions. But while I find that integrity comes up surprisingly often, really hard decision-theoretic cases come up about as rarely as you’d expect.

A convenient thing about this form of integrity is that it basically means behaving in the way that I’d want to claim to behave in this blog post. If you ask me “doesn’t this imply that you would do X, which you only refrained from writing down because it would reflect poorly on you?” then you’ve answered your own question.

III.

Why would I do this? At face value it may look a bit weird. People’s expectations about me aren’t shaped by a magical retrocausal influence from my future decision. Instead they are shaped by a messy basket of factors:

- Their past experiences with me.

- Their past experiences with other similar people.

- My reputation.

- Abstract reasoning about what I might do.

- Attempts to “read” my character and intentions from body language, things I say, and other intuitive cues.

- (And so on.)

In some sense, the total “influence” of these factors must add up to 100%.

I think that basically all of these factors give reasons to behave with integrity:

- My decision is going to have a causal influence on what you think of me.

- My decision is going to have a causal influence on what you think of other similar people. I want to be nice to those people. But also my decision is correlated with their decisions (moreso the more they are like me) and I want them to be nice to me.

- My decision is going to have a direct effect on my reputation.

- My decision has logical consequences on your reasoning about my decision. After all, I am running a certain kind of algorithm and you have some ability to imperfectly simulate that algorithm.

- To the extent that your attempts to infer my character or intention are unbiased, being the kind of person who will decide in a particular way will actually cause you to believe I am that kind of person.

- (And so on.)

The strength of each of those considerations depends on how significant each factor was in determining their views about me, and that will vary wildly from person to person and case to case. But if the total influence of all of these factors is really 100%, then just replacing them all with a magical retrocausal influence is going to result in basically the same decision.

Some of these considerations are only relevant because I make decisions using UDT rather than causal decision theory. I think this is the right way to make decisions (or at least the way that you should decide to make decisions), but your views my vary. At any rate, it’s the way that I make decisions, which is all that I’m describing here.

IV.

What about a really extreme case, where definitely no one will ever learn what I did, and where they don’t know anything about me, and where they’ve never interacted with me or anyone similar to me before? In that case, should I go back to being a consequentialist jerk?

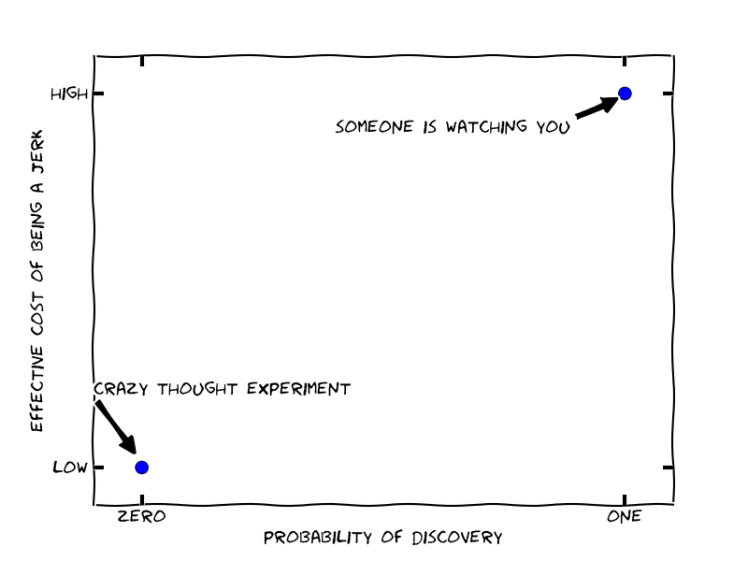

There is a temptation to reject this kind of crazy thought experiment—there are never literally zero causal effects. But like most thought experiments, it is intended to explore an extreme point in the space of possibilities:

Of course we don’t usually encounter these extreme cases; most of our decisions sit somewhere in between. The extreme cases are mostly interesting to the extent that realistic situations are in between them and we can usefully interpolate.

For example, you might think that the picture looks something like this:

On this perspective, if I would be a jerk when definitely for sure no one will know then presumably I am at least a little bit of a jerk when it sure seems like no one will know.

But actually I don’t think the graph looks like this.

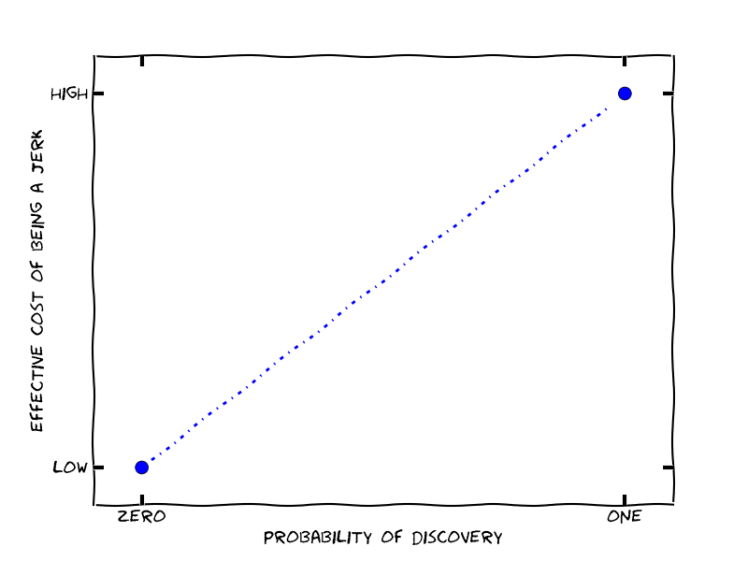

Suppose that Alice and Bob interact, and Alice has either a 50% or 5% chance of detecting Bob’s jerk-like behavior. In either case, if she detects bad behavior she is going to make an update about Bob’s characteristics. But there are several reasons to expect the 5% chance will have a 10x larger update if it actually happens:

- If Alice is attempting to impose incentives to elicit pro-social behavior from Bob, then the size of the disincentive needs to be 10x larger. This effect is tempered somewhat if imposing twice as large a cost is more than twice as costly for Alice, but still we expect a significant compensating factor.

- For whatever reference class Alice is averaging over (her experiences with Bob, her experiences with people like Bob, other people’s experiences with Bob…) Alice has 1/10th as much data about cases with a 5% chance of discovery, and so (once the total number of data points in the class is reasonably large) each data point has nearly 10x as much influence.

- In general, I think that people are especially suspicious of people cheating when they probably won’t get caught (and consider it more serious evidence about “real” character), in a way that helps compensate for whatever gaps exist in the last two points.

In reality, I think the graph is closer to this:

Our original thought experiment is an extremely special case, and the behavior changes rapidly as soon as we move a little bit away from it.

At any rate, these considerations significantly limit the applicability of intuitions from pathological scenarios, and tend to push optimal behavior closer to behaving with integrity.

This effect is especially pronounced when there are many possible channels through which my behavior can effect others’ judgments, since then a crazy extreme case must be extreme with respect to every one of these indicators: my behavior must be unobservable, the relevant people must have no ability to infer my behavior from tells in advance, they must know nothing about the algorithm I am running, and so on.

V.

Integrity has one more large advantage: it is often very efficient. Being able to make commitments is useful, as a precondition for most kinds of positive-sum trade. Being able to realize positive-sum trades, without needing to make explicit commitments, is even more useful. (On the revenge side things are a bit more complicated, and I’m only really keen to be vengeful when the behavior was socially inefficient in addition to being bad for my values.)

I’m generally keen to find efficient ways to do good for those around me. For one, I care about the people around me. For two, I feel pretty optimistic that if I create value, some of it will flow back to me. For three, I want to be the kind of person who is good to be around.

So if the optimal level of integrity from a social perspective is 100%, but from my personal perspective would be something close to 100%, I am more than happy to just go with 100%. I think this is probably one of the most cost-effective ways I can sacrifice a (tiny) bit of value in order to help those around me.

On top of that:

- Integrity is most effective when it is straightforward rather than conditional.

- “Behave with integrity” is a whole lot simpler (computationally and psychologically) than executing a complicated calculation to decide exactly when you can skimp.

- Humans have a bunch of emotional responses that seem designed to implement integrity—e.g. vengefulness or a desire to behave honorably—and I find that behaving with integrity also ticks those boxes.

After putting all of this together, I feel like the calculus is pretty straightforward. So I usually don’t think about it, and just (aspire to) make decisions with integrity.

VI.

Many consequentialists claim to adopt firm rules like “my word is inviolable” and then justify those rules on consequentialist grounds. But I think on the one hand that approach is too demanding—the people I know who take promises most seriously basically never make them—and on the other it does not go far enough—someone bound by the literal content of their word is only a marginally more useful ally than someone with no scruples at all.

Personally, I get a lot of benefit from having clear definitions; I feel like the operationalization of integrity in this post has worked pretty well, and much better than the deontological constraints it replaced. That said, I’m always interested in adopting something better, and would love to hear pushback or arguments for alternative norms.

Overall this seems like it’s on the right track – I do something similar. But I think the decision rule that disfavors things people would think worse of you if they knew about needs a bit more work. In particular, even if you scope-limit it to matters of integrity, it permits social expectations to pressure you into arbitrary actions by declaring them important signals of integrity. This seems like it could be a very bad constraint, making it quite difficult to believe unusual things on e.g. justice and group affiliation.

Something like the Kantian categorical imperative, where you’re considering what maxims you’d like to generalize to interactions among any two rational beings seems like a promising patch, since that means you can rule out wrong judgments by society in a principled way that doesn’t involve asserting *personal* privilege.

My inclination is that if people wouldn’t want to be my ally if I held belief X, then that *should* be a reason to avoiding holding belief X (rather than merely pretending I don’t hold it). In most cases I think this cost is not high enough to overcome the benefits of actually trying to figure out the truth. I agree that not concealing your beliefs makes it *more* difficult to hold unusual beliefs, but I don’t agree that it makes it difficult.

I also think that most of the time society cares more about what we say then what we believe, and on this point I am more often willing to give in to social pressure on issues that I consider relatively unimportant. But that feels kind of orthogonal to integrity.

I could be argued out of this view, but it certainly don’t seem obvious.

Should be a reason over and above the evidential value of their wanting not to ally?. logic doesn’t work like that!. And social norms push directly against logic all the time. You have to choose between them. Mostly logical beliefs are apologism, and are not mostly truth tracking.

Like Ben, I’m a little uncertain whether the rule “do things that you’d want people to have known about” is quite right. One obvious example where this is potentially too strong, as Ben mentions, is unpopular convictions — you might not actually want people to know you hold them, so your rule would require you to self-modify to not have those convictions any more. It might also be too weak to cover everything we mean by integrity. Integrity seems to include some notion of internal coherence, of parts matching each other, that isn’t really about transparency to others (or even hypothetical transparency), but is about being smooth/whole/consistent within oneself.

This rule suggests that having unpopular convictions (that would make people think twice about allying with you) should be considered a cost, and I (tentatively) endorse that implication. I don’t think the rule requires you to abandon such convictions though, it depends on how you weigh up the costs and benefits. I would personally feel bad about allying with someone under false pretenses about my beliefs, but I would also feel bad about allying with someone who considered “right” belief to be a precondition for collaboration.

I definitely agree that this doesn’t really capture everything we mean by “integrity.” I tried for a little while to come up with a better name and I couldn’t, I’m interested in any suggestions.

Huh. Something about your (Sarah’s) response made me more worried about the underlying post. In particular, I wonder whether this might be a desideratum in a moral system:

If you’re considering hiding Anne Frank’s family in your attic, and you generate the objection, “my Nazi neighbors, whose cooperation in many things in life I highly value and benefit from, would be really disappointed in me if they found out I wasn’t on board with the plan to murder all the Jews,” the *moral* weight of this objection (as opposed to the practical weight) should come out to zero or nearly zero.

I am not sure Paul’s thing does that. I am worried that it is too humble to do that.

I’m not sure this objection is coherent – it feels more like vague gesturing at a thing than a well-targeted attack on a weak point.

I don’t think I endorse a distinction between prudential and moral reasons. To the extent I do, then I would implement it by separating out types of consequences, and would say that the Nazi-neighbors objection has moral weight iff cooperation with the Nazi neighbors was important for moral ends.

This kind of phenomenon doesn’t seem inherently troubling to me. Suppose that Alice and Bob have profound disagreements about what one ought to do, and find each others’ views abhorrent. I think that we should have norms that make it possible for them to cooperate (to the extent that their values are not 100% opposed, in which case there are no gains from trade and its hard to see how my recommendation could ever recommend cooperation).

This example does have something in common with the guess-a-number-between-1-and-20 example though. Namely, suppose that from your Neighbors’ perspective you are indistinguishable from 20 other households that might be hiding Anne Frank’s family. introducing uncertainty about which of the 20 households is hiding them genuinely undermines the position of your Nazi neighbors, in a way that it wouldn’t if they had perfect insight into your decision. When considering hiding Anne Frank’s family, I think that you should take account of this weakening of the Nazi cause (just like you shouldn’t assume you will win at the guess-a-number game) and weigh it against the benefits of cooperation with the Nazis. And when evaluating the weakening of the Nazi cause you should consider the losses to your neighbors from the inability to cooperate with the 19 households that look just like you.

I agree that these cases seem to point to something tricky which isn’t being handled correctly. I don’t (yet) share the intuition that there is a problem related to humility.

You seem to be thinking of moral considerations as a certain subset of values or ends that might be weighed against other end. I mean to point to something else: There are different modes of analysis, and one mode is the moral mode. You’d never talk of weighing decision-theoretic considerations against other considerations – you have to include other considerations IN your decision-theoretic analysis! Same for moral analysis of actions.

Let me back up a little bit. I am (a very complex version of) Pac-Man. I want to eat dots. “Morality” is simply that which gets me the most dots. This is what consequentialism is, no? With something more elaborate standing in for “dots.”

I agree with Paul that moral vs. practical makes no sense in this context. An improvement is simply something that gets you more dots to gobble.

You ought to place some weight on changing your opinions about the world to match others’, simply because you have uncertainty in your own opinion. (This does not imply toxic conformity, but only common sense. If a crowd gets off a train and moves left, you can reasonably conclude that the exit is likely to be on the left.) You get more dots to eat if you listen to others. But this has nothing to do with “cooperation.”

Paul’s rule, in the case of “hiding Jews in your attic”, would say that you should act as you would if the Nazis had already known that you would be the kind of person who would hide Jews in your attic. Given that political opponents to the Nazis did not fare well (the saying goes “First they came for the socialists”), you would not get any delicious dots if the Nazis knew, and therefore your integrity constraint doesn’t allow you to hide Jews, and this seems quite wrong.

The issue here is that Paul’s rule is against underhanded dealing. It favors the candid, “what you see is what you get” person. A person who would not do what he would not want to be publicly known as evidence of his character. My mental stereotype is that this is an English gentleman.

An English gentleman is certainly better than a crook! But underhanded dealing genuinely can be ethical. The actual Holocaust (not as a thought experiment but as a historical event) is full of examples where *wiliness* was heroic, where underhanded dealing was heroic, where sneaking around was heroic. Oskar Schindler was a Nazi spy, who initially protected Jews for convenience alone. An overly restrictive, priggish concept of integrity would have said he was a bad person and not given him the chance to become a hero. There’s something about leaving room for the wily opportunist and the last-minute defector against evil. Like, yeah, you broke your word, but at a certain point you realized that you’d given your word to something *awful* and you didn’t care any more.

When Huck Finn lies to protect Jim, and feels guilty about it, and certainly wouldn’t want to be *known* as the kind of person who would do so, that’s a kind of “defecting towards conscience” and I think Paul’s rule would penalize it.

I think what the definition might need is some kind of reciprocity. It’s asymmetrical: you, the person of integrity, want to act as you would have acted if you were known by *people*. Which people? Any people. Not weighted by how ethical they are. Kant’s thing at least imagines a community of *rational* people and rules for that hypothetical community.

I definitely agree that something seems wrong in these cases, I’m hoping to think about it a little bit more, and hopefully there is a nicer statement that gets at the same intuitions but is less problematic. Maybe there isn’t.

I expect to disagree with your/Ben’s diagnosis, in particular I’m initially skeptical about reciprocity being a good answer. I also feel that it’s correct to consider underhanded dealing a cost, I think the only error is estimating how large a cost it should be.

Here is a case that seems to me to isolate the problem.

Suppose that the Reds and Blues are fighting. Twenty Red soldiers are invading a facility, one of them is carrying an explosive. The Blues are able to kill one Red soldier, and would prefer kill the one carrying an explosive. Once each Red soldier is inside the facility, they can either do a modest amount of damage—or if they are carrying an explosive they can detonate the explosive to do a lot of damage.

If I am the soldier with an explosive, after reaching the facility it is clearly incorrect for me to say “If the Blue soldiers knew that I was going to detonate this explosive they would have shot me instead. So I should do a modest amount of damage (since the net effect is neutral on the facility, and surviving is better for me personally).” This is clearly not what the rule recommends. We should regard my decision as letting the Blues know that I am the kind of person who would use the explosive if I had it, not letting them know that I have the explosive.

Now suppose that using the explosive involves dying, and only one Red soldier is willing to use the explosive given that. I think this case should clearly be treated identically to the previous one, even though letting the Blue soldiers know “that I am the kind of person who would detonate the explosives if I had them” would let them know that I must have the explosives.

To go even further, suppose that only one Red soldier is a consequentialist who acts with integrity; only this soldier would actually follow through with the plan rather than defecting (I’m not claiming this is realistic), and so they are guaranteed to be the one who has the explosives. if the Blues knew which one it was they would shoot them. I think that this case should also be handled identically to the previous two.

This is definitely a problem on a literal reading of the heuristic, but I feel like it is consistent with the spirit, and so I’m optimistic there is a simple patch. This is clearly a problem independently of whether the Blue soldiers behave with integrity. I also feel like this is the main problem in the Nazi cases, or at least it doesn’t seem worth considering those cases in more detail when there is this simplified scenario that also poses a problem. (This is the kind of thing I was trying to point to with the guess-a-number example.)

To clarify: I think that you can handle the second case in my thought experiment (where only one person is willing to die) by explicitly calling “preferences” part of your situation; when considering detonating the explosives, you imagine that it lets people know that you are the kind of person who would decide to detonate the explosive if you were willing to die today, but not that it lets them know that you were willing to die today.

This seems to get you some of the way to sanity in the Nazi case. If you hide Anne Frank’s family you don’t need to imagine that you are letting your neighbors know that you are a political dissident. You are letting people know that *if* you were a political dissident (or had drastically opposed views about what is good, or whatever underlying difference it is), *then* you would behave subversively.

This doesn’t get you all the way to sanity, since e.g. your Nazi neighbors might look skeptically on anyone who would behave subversively *if* they were a political opponent (and it doesn’t at all handle the third case in my thought experiment). But it seems like it is pointing in the right direction / getting closer to my intuitions.

Thanks, this seems clearer, closer to the right answer, and is also helping me work out my own objection better.

My current intuition is that the problem lies somewhere in the distinction between cooperative aspects of relationships where you are trying to reveal info, and adversarial aspects of relationships where you are trying to conceal info. I suspect that a complete and correct version of this principle would address that distinction more explicitly, rather than treating each interaction as a one-off to be calculated on the fly.

This isn’t quite the distinction between enemies and allies. Enemies can cooperate on, e.g., limiting the scope of conflict, keeping lines of communication open for surrenders, etc. This is why spies are treated differently than soldiers; spies aren’t just enemies but unlawful enemies.

I like this take on integrity and I think the bit where you bite the bullet and accept the “you shouldn’t hold socially unacceptable beliefs, all else equal”. I don’t quite agree with it, but I think there’s something there that’s really hard to not just dismiss from a rationalist perspective.

Here’s my take on it:

It’s all about eating the most pacman dots, as Sarah put it, and that means there really are right and wrong answers on a lot of what people call “incompatible values”. A lot of times people will actually change their values upon learning more, and some values really are more informed than others. The “hiding jews” example isn’t as clean and clear here, so I’ll use a different one.

The thing normally referred to by “beating your wife” is bad. However, the badness isn’t inherent in the impact itself and there are other cases that might look superficially similar but be quite different. For example, if Bob and his wife are into BDSM and in particular “impact play” it might actually be a good thing for them. If it is and they run in the right circles, this can be something people won’t judge them negatively for. If they run in more socially conservative circles, they might round it off to “Bob beats his wife” and therefore not want people to share that information.

On a first pass, it might seem that your definition of integrity encourages them to not do BDSM if they have socially conservative friends. However since there is, in fact, a difference between consensual impact play and old fashioned wife beating, it’s worth distinguishing them here too. Instead of doing less that would look bad to people if they saw it, do less that would look bad to people if they knew what was going on. In other words, even if it sounds bad you don’t have to not strike your wife so long as people would realize it’s a good thing if they were to understand what is actually happening. You’re not trying to hide “strikes wife”, you’re trying to prevent someone who cannot comprehend “consensual impact play” from falsely concluding that you’re a wife beater.

This solves the apparent conflict between “social disapproval is not an argument” and “integrity says you probably shouldn’t be doing things that you feel like hiding from people”. You aren’t doing things you feel like you have to hide, because you’re not hiding these things, you aren’t using the threat of lynching to convince yourself that 2+2=5, but you still do have to think things through harder when they’re socially unacceptable.

The way it works is that you work toward them understanding you while being careful not to let them come to think they understand you in ways that are inaccurate and paint you as a bad guy. For example, if Bob is asked “do you hit your wife?”, a “yes” answer would be dishonest because he’s knowingly allowing them to conclude he’s a wife beater and a bad person when he is not and they disagree respectively. A better answer would be “how awful do you think I am?”, because anyone that understands BDSM can say “no, you could be a good person and into BDSM” (which Bob can then confirm) while anyone that cannot comprehend that there is a difference won’t be accidentally deceived into thinking Bob is a bad guy.

The reason this forces you to rethink anything socially disapproved of is that if someone understands BDSM and still thinks that it’s bad for reasons that Bob doesn’t get, then Bob is going to admit to the guy what he does and will face the consequences of it. It makes you really put your money where your mouth is on what is okay and what isn’t. You can’t just get away with insisting “You can’t handle the truth! If you understood you’d agree with me!” – you actually have to allow it to be tested.

This allows us to keep all the desiderata of integrity without crippling us to be conformists.

I think that in practice, people typically defend conservative norms by choosing not to listen to supposedly relevant details, to ’round it off’, as you say, rather than risk believing a complicated and subtly wrong argument (or simply rather than risking entering a nonconforming state, with its attendant disadvantages). Thhis seems related to the Cluster Thinking endorsed by Holden on his blog.

How to make the right precommitments and not to be bullied by the precommitments of ohers is a major part of this decision theory game.

I think there is a difference between rounding off X for computational reasons, and being resistant to arguments against X for fear that we may incorrectly perceive them as compelling or for fear of being judged for considering them seriously. In particular, if you are rounding off X for computational reasons, you will still entertain arguments against X whenever they are suggested by anyone you respect enough to have serious discussions with.

I agree that this is a low-energy approximation. At sufficiently high energies this heuristic isn’t even coherent and we eventually need to fall back to UDT, or (in the cases where the philosophy is hard) our best guesses about the decision-theoretically correct moves. I think it will tend to make qualitatively similar decisions to the heuristic, but in some cases it seems a little bit tricky.

That’s a very interesting post with many additional arguments for behaviors I’ve started to favor in recent years.

In the slightly different context of values spreading, I’ve distilled a hierarchy of strategies from a post by Brian Tomasik. The idea is similar except that “integrity” suggest something rather undirected while in the case of cooperative behavior there is always a cooperation partner and a partially shared goal.

Here, situations such as the BDSM problem or the hiding jews problem would be resolved because, based on my moral goals, I could choose to cooperate on the issue with my wife or the jews and not with the conservatives or the nazis.

So toward my cooperation partners I would behave with perfect integrity with anything that relates however tenuously to our shared project. The main problem becomes to behave in such a way as to encourage potential cooperation partners to enter into cooperation with me. I think your notion of integrity is a good guide to that, but in the cases of nazis or conservatives (group A) on the given topics, I would care greatly about other, incompatible cooperation projects (with the jews or my wife, group B) and would sacrifice my chances at cooperating with group A for cooperating with group B.

Does that make sense to you?

Reblogged this on Quaerere Propter Vērum.